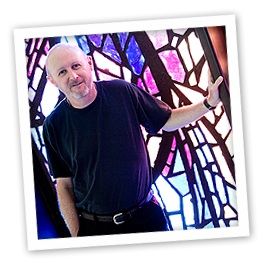

Professor Randy Harris is spiritual director in the Department of Bible, Missions and Ministry at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. He will be at speaking at Pepperdine in Elkins Auditorium at 7 p.m. on Sunday for the first night of the 2012 Veritas Forum.

Graphic: This year’s Veritas Forum at Pepperdine University is titled: “Radical Conversations — Engaging a Multi-Faith World.” What do you hope to communicate during your talk? What are you most excited about getting to share?

Randy Harris: What I want to address is what I think is Christianity’s greatest critic, which is Friedrich Nietzsche — I think the greatest critic of Western Culture and the greatest critic of Christianity. I think that Christians have to be able to answer Nietzsche in order to have a credible Christianity. Most, at least a lot, of Christian theologians don’t pay a lot of attention to Nietzsche, but I find him a really formidable thinker and I have to try and make a case for Christianity countering the Nietzsche argument.

G: What do you think is his strongest point that needs to be addressed?

RH: Part of Nietzsche’s complaint about Christianity is that it does not take this world seriously enough. It’s a religion of another world — of an afterlife. He thinks it’s “life-denying.” It denies our present life. So, I try to think through how you can have a Christianity that is as affirming of life as Nietzsche was. It’s a challenge.

G: How do Christian students “engage in a multi-faith world” when they go to a religious school and are usually surrounded by people of like mind? How do they prepare for these experiences in life after school?

RH: I think a big part of it is the openness — being open to conversation. You can take classes in world religions and learn things about other faiths, but the best way to learn about them is to let people who are practitioners of those faiths tell you about their faiths. Having friends from a variety of religious traditions and letting them tell you what their religion means to them and how they interpret the world [is] the best way to engage this world and understand your own faith and explain to them how yours operates.

G: Inter-faith discussion holds a commonality of belief between those involved. How do you think Christians can better engage people of doubt or of no faith at all?

RH: Everybody has some faith commitments. That is, there are some things you believe to be true or base your life on that you cannot absolutely ground. So, conversation is asking, “Are the things that you’re accepting as true, that you can’t ground, worthy of the weight you put on them?” I think that’s the point of this kind of engaged discussion.

G: Any dialogue involves some give and take on any given position. How do you think Christians should determine what to give on, and how much they should give in inter-faith discussions?

RH: Every faith has certain core values, which are non-negotiable. I think there are some other things that are not as fundamental to that faith. I think it’s pretty hard to negotiate, or compromise on those core values. Part of religion is finding out what those fundamental commitments are. Other things, I think, there’s room for movement on. One way to ask that about Christianity is to ask, “What do you have to believe to be a Christian, and what are the things you can believe as a Christian that are not endemic or central to that faith?”

G: To what extent do you think that Christians can utilize the same strategies of inter-faith dialogue for resolving disagreements within a particular faith community?

RH: There are a lot of similar things, primarily, the whole notion of being open to conversation, open to truth, open to the possibility you might be wrong — what a philosopher might call “epistemologically superlative,” which basically means, “OK, there’s a possibility I’m wrong.” That’s going to be crucial to the dialogue whether it’s with another faith or in the interior of your faith.