[youtube valKIEowHXY]

If you think back to the last time you saw a sea otter during a beach outing, chances are you can’t remember it. And that’s not because sea otters are easily forgettable or go to extensive lengths to avoid humans. It’s because there aren’t any.

At first, it might seem as if this problem is nothing more than a disappointing lack of cute sea creatures in the Southern California area. But the truth is, the problem is much greater. So great, in fact, that the natural ecosystem of Southern California waters is threatened to the point of survival, a problem that has dire consequences for both sea life and people in the Southern California region.

Brian Meux is the Marine Programs Manager at Los Angeles Waterkeeper, a non-profit organization that came about in 1993 and whose mission is “to protect and restore Santa Monica Bay, San Pedro Bay and adjacent waters through enforcement, fieldwork, and community actions,” according to their website.

Meux’s main line of work involves educating and involving the public about the importance of kelp restoration, citing a lack of understanding of it’s importance as one of the main barriers to getting the public involved.

“With this issue it’s so far removed from people’s lives and doesn’t effect their personal day-to-day operations,” Meux said. “We can get the community involved through outreach and education and those are the main aims of the kelp project.“

So what exactly are the implications of depleted kelp forests in Southern California? Do they effect the general population? Meux says most definitely.

“[Southern California has] a few fisheries that are directly dependent on kelp forests being productive and stable,” Meux said. “The urchin, lobster, crab, etc., all come from kelp forests. You would [also] see an indirect effect on schools [of fish] from the barracuda to tuna and a general decline in biomass and diversity.”

David Green, a Professor of Chemistry at Pepperdine University and certified Divemaster expressed a mixed opinion about consumption of marine life, noting an increased level of awareness but also an apathy towards taking action.

“Attitudes toward and awareness of the ocean has been steadily improving since the 1970s,” Green explained. ” The realization by local sport and consumer fisheries that the resource is not unlimited has improved consumption from the ocean. However, consumers are mostly unwilling to pay the higher price on seafood that would result from limiting fishing (both fish and invertebrates) so change comes slowly.”

More alarming though, is the fact that the impact extends beyond depletion of delicacies for human consumption, ultimately influencing the greater Southern California economy.

“If you have an empty or degraded ocean you will have decreased tourism, decreased recreation, decreased educational opportunities and that has it’s own economic impact,” Meux said.

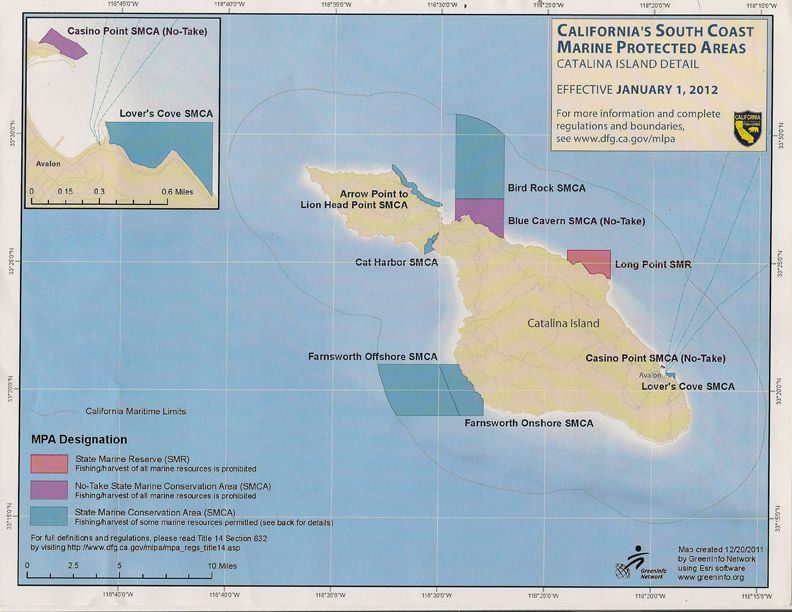

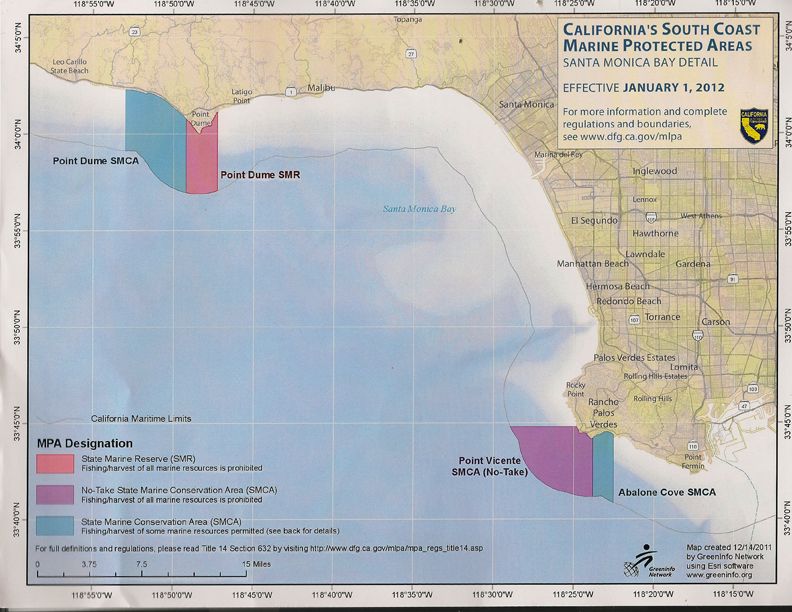

Despite the seemingly dismal outlook that has persisted for years, Meux does acknowledge initiatives that are in place to assist with the restoration, one of the main ones being Marine Protected Areas, which is “an area of the ocean where consumptive human activities such as fishing are limited or restricted in order to protect or conserve marine life or habitats.“

Los Angeles MPA’s include Point Dume State Marine Reserve, Point Dume State Marine Conservation Area, and the Point Vicente and Abalone Cove State Marine Conservation Areas. The restrictions vary by area.

While the Marine Protected Areas work to keep and slowly restore the current balance of the ecosystem that has managed to survive, there is still a lot of work to be done to rebalance what has been altered through the past century.

And this is where the sea otters come in. Sea otters began disappearing as far back as the fur trade in the late 1800’s. Their numbers were so scare in the 1980’s that federal regulations were put in place to keep the Southern California sea otter from going extinct.

“In the late 80’s the feds jumped in there and said ‘Ok, we have a handful of otters along the coast. If there was an oil spill along the mainland coast, then these otters are gone so we need to spread out the sea otter as best as we can,’” Meux explained.

“During that time U.S. Fish and Wildlife worked with local scientists to capture otters and take them to Saint Nicholas Island [where they wouldn’t be affected should there be an oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara]. It was a well-intentioned project, but they killed a lot of otters doing that.”

The high number of otter deaths as a result of their relocation caused federal agencies involved with moving sea otters to cease their activity. Unfortunately, there was a “no otter zone” implemented throughout the rest of Southern California that still remains to this day, a measure that allows for any otter that travels south of Santa Barbara to be picked up and be taken back to Saint Nicholas Island. This “no otter zone” is the ultimate reason for lacking kelp beds throughout the region.

In a nutshell, otters are responsible for maintaining the urchin population that feeds on kelp beds. The lack of sea otters over the past decades has created a significant increase in urchin barrens throughout Southern California, severely depleting the kelp beds and forests that are necessary for a healthy ocean ecosystem.

Kelp forests remain one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems in the world, as they work to provide shelter and nutrients, creating hospitable environments for animals and algae and essentially becoming a nursery ground for fish, urchins and other sea life such as otters and seals. Depletion of these kelp beds inhibits the ability of the ground level of the food chain to function properly; essentially creating an ocean environment that cannot sustain life, impacting not online marine life but a significant number of humans that rely upon fish for food on a daily basis.

Meux alluded to commercial organizations as the ultimate cause of this increasing imbalance.

“Think about who is threatened by the otter in Southern California; commercial urchin fisheries and the oil industry,” Meux explained.

Federal laws that mandate damage payments by oil industries should there be an oil spill and commercial urchin fisheries that rely on an excessive amount of urchins are the two main advocates for the “no otter zone” despite it’s harmful impact on the greater marine ecosystem.

“It’s a special interest group that is only thinking about their personal pocketbooks,” Meux said. “And it’s interesting because if we did have otters in full density in Southern California there would be a very healthy fishery,” Meux continued. “There would be lush kelp forests and over 800 species of biodiversity.”

Green expressed a slightly different and more optimistic view about the role of oil companies as it relates to marine protection.

“Oil producers are increasingly more conscious of protecting the marine environment than 25 years ago,” Green commented. “The cost of cataclysmic failure is so high that is more economic to produce oil with protections in place.”

His optimism is not unfounded. Sea otters have been slowly returning to Southern California. Approximately 3,000 are in Southern California to date and conservation organizations may hear from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services as early as the end of this year about whether or not there is going to be a ban of the “no otter zone.”

“Otters have been slowly moving south through natural population expansion and Fish and Wildlife has been looking the other way,” Meux explained. But there is still a long way to go.

“Even if the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does allow otters into Southern California waters it would still take about 20 years for the otters to reach San Diego, Mexico and the Baja which is their former historic range,” Meux said.

Southern California restoration efforts are far from over, but every victory counts, no matter how small. So far approximately 10 acres have been restored off the coasts of Malibu and Palos Verdes. Funding is minimal for kelp and ocean restoration, so organizations such as LA Waterkeeper rely heavily on grants, donations and volunteers to keep the operation running, although Meux does note a small but dedicated staff and volunteer crew that allows restoration efforts to continue year round.

“We use volunteer scuba divers from the community to come out on our boat and relocate sea urchins so we get the urchin barrens down to densities that are normal,” Meux said.

The Montrose Settlements Restoration Program, initiated after the Montrose company was caught pumping large amount of DDT into Southern California water and damaging a significant portion of the ecosystem, has also provided funding to bigger organizations that work with LA Waterkeeper to aid in the restoration initiative. Waterkeeper code mandates that LA Waterkeeper is not allowed to take money directly from a pollutant organization.

Holding companies that pollute marine habitats responsible for the damage they cause is also high on the priority list of LA Waterkeepr and similar organizations, with high hopes that decreasing pollution with increase marine vitality.

“California is unique because we have these giant kelp forests and people come from all over to see them healthy and see the giant black sea bass. People go to Monterey just to see sea otters,” Meux said. “We can either decide to let these habitats keep declining and degrading or we can do something about it.”

To see volunteer opportunities related to kelp and marine restoration, click here.